Feel good thread...

- Thread starter skidadl

- Start date

Genghis Khan

The worst version of myself

- Joined

- Apr 7, 2013

- Messages

- 46,707

Man...

Irving Cowboy

DCC 4Life

- Joined

- Feb 7, 2014

- Messages

- 3,713

Irving Cowboy

DCC 4Life

- Joined

- Feb 7, 2014

- Messages

- 3,713

World War II bomber crash left 11 dead. Four are finally coming home.

All 11 men aboard the bomber were killed. Their remains, deep below the sea, were designated as non-recoverable. That changed in 2023.

World War II bomber crash left 11 dead. Four are finally coming home.

By Michael Hill, The Associated Press

May 26, 2025, 01:56 PM

Ten crew members of Heaven Can Wait, which went down in the waters of Papua New Guinea in 1944. Staff Sgt. Eugene Darrigan is top row, second from right. Bottom row, from left are 2nd Lt. Donald Sheppick, 1st Lt. Herbert Tennyson, and, far right, 2nd Lt. Tomas Kelly. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency via AP)

As the World War II bomber Heaven Can Wait was hit by enemy fire off the Pacific island of New Guinea on March 11, 1944, the co-pilot managed a final salute to flyers in an adjacent plane before crashing into the water.

All 11 men aboard were killed. Their remains, deep below the vast sea, were designated as non-recoverable.

Yet four crew members’ remains are beginning to return to their hometowns after a remarkable investigation by family members and a recovery mission involving elite Navy divers who descended 200 feet (61 meters) in a pressurized bell to reach the sea floor.

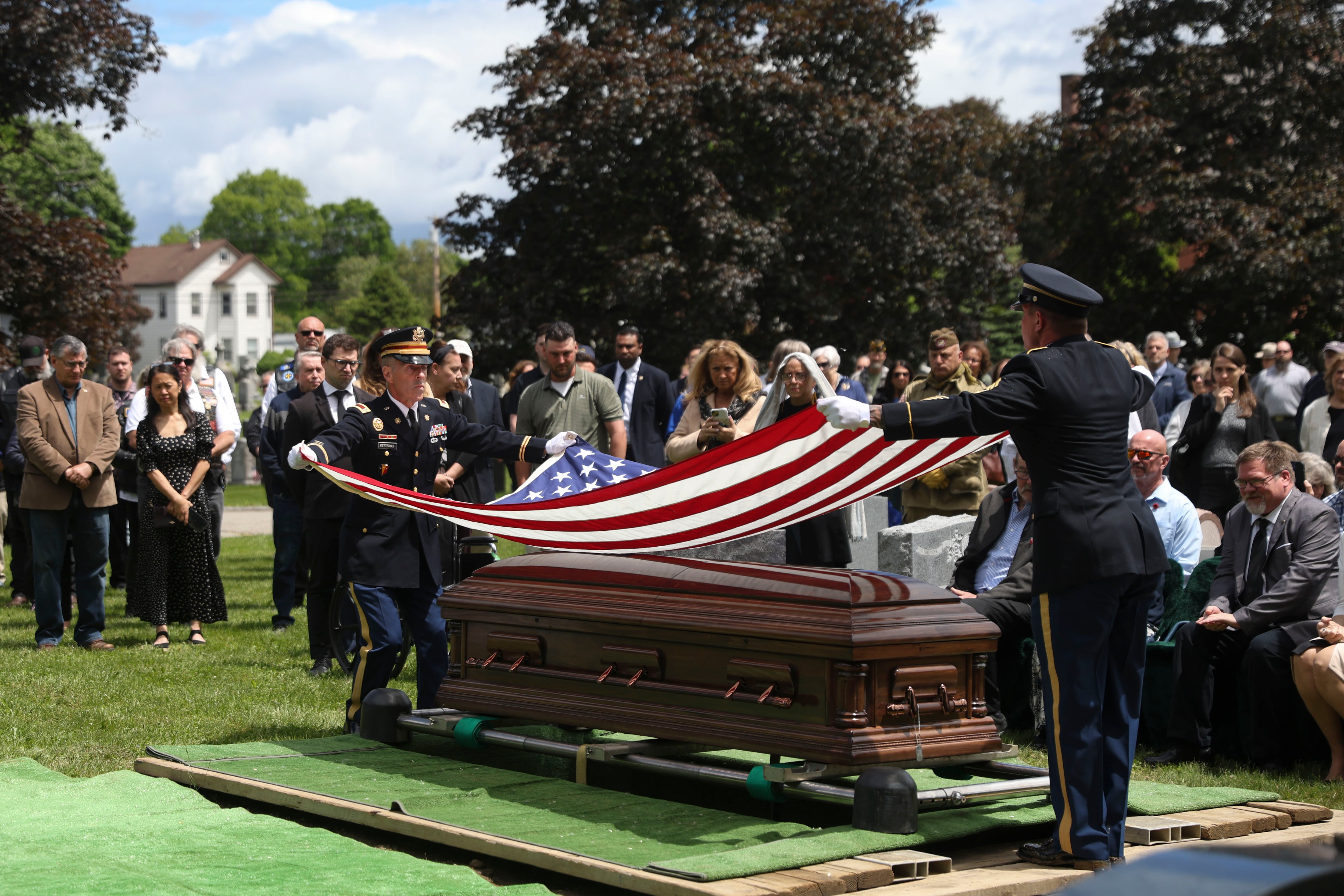

Staff Sgt. Eugene Darrigan, the crew’s radio operator, was buried with military honors and community support on Saturday in his hometown of Wappingers Falls, New York, more than eight decades after leaving behind his wife and baby son.

An American flag is folded during the interment of WWII U.S. Army Air Forces Staff Sgt. Eugene Darrigan, May 24, 2025, in Wappingers Falls, New York. (Heather Khalifa/AP)

The plane’s bombardier, 2nd Lt. Thomas Kelly, was to be buried Monday in Livermore, California, where he grew up in a ranching family. The remains of the pilot, 1st Lt. Herbert Tennyson, and navigator, 2nd Lt. Donald Sheppick, will be interred in the coming months.

The ceremonies are happening 12 years after one of Kelly’s relatives, Scott Althaus, set out to solve the mystery of where exactly the plane went down.

“I’m just so grateful,” he told The Associated Press. “It’s been an impossible journey — just should never have been able to get to this day. And here we are, 81 years later.”

March 11, 1944: Bomber Down

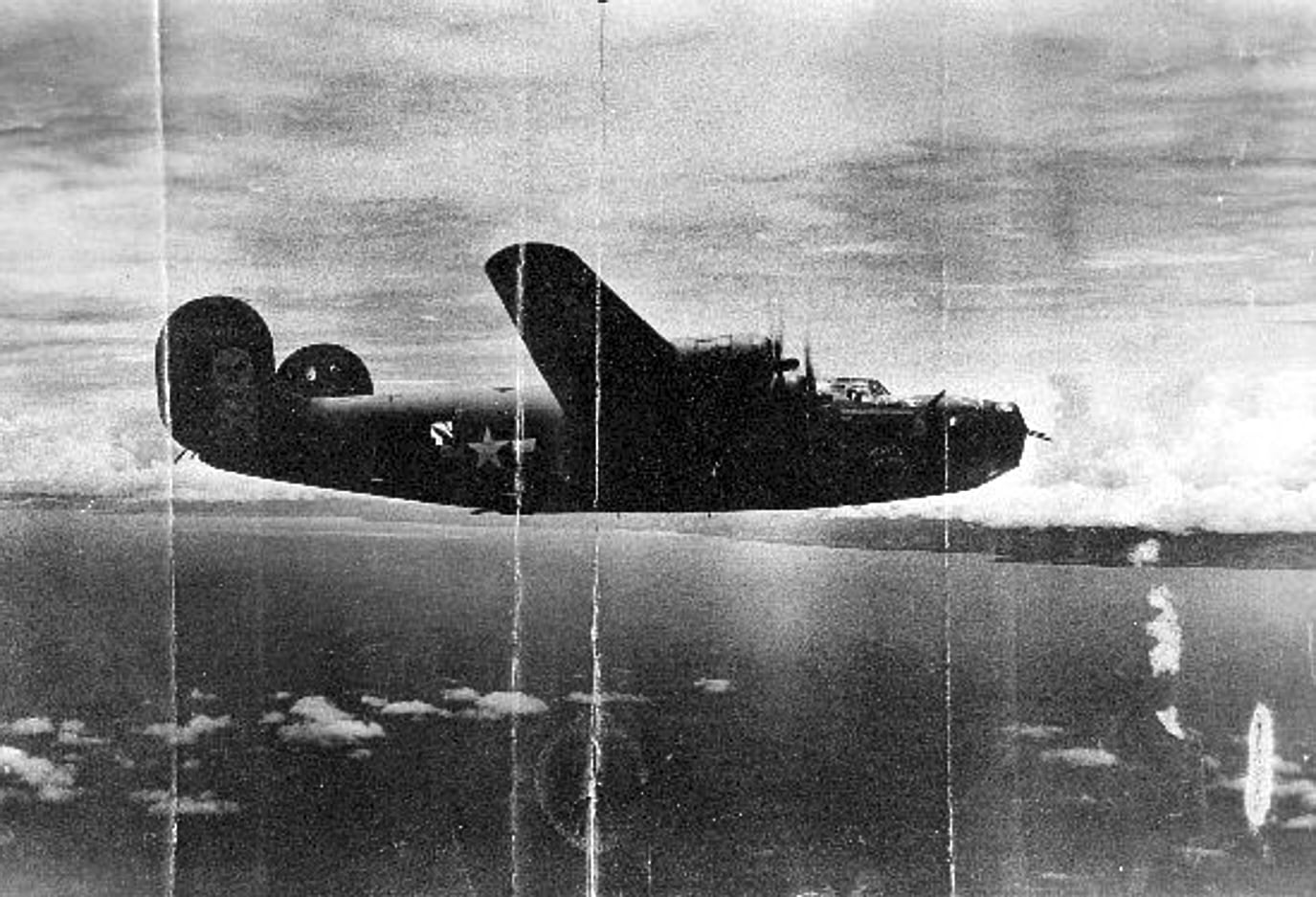

The Army Air Forces plane nicknamed Heaven Can Wait was a B-24 with a cartoon pin-up angel painted on its nose and a crew of 11 on its final flight.

They were on a mission to bomb Japanese targets when the plane was shot down. Other flyers on the mission were not able to spot survivors.

Their wives, parents and siblings were of a generation that tended to be tight-lipped in their grief. But the men were sorely missed.

Sheppick, 26, and Tennyson, 24, each left behind pregnant wives who would sometimes write them two or three letters a day. Darrigan, 26, also was married, and had been able to attend his son’s baptism while on leave. A photo shows him in uniform, smiling as he holds the boy.

Diane Christie wears a necklace with a photograph of her uncle, WWII U.S. Army Air Forces 2nd Lt. Thomas Kelly. (Godofredo A. Vásquez/AP)

Darrigan’s wife, Florence, remarried but quietly held on to photos of her late husband, as well as a telegram informing her of his death.

Tennyson’s wife, Jean, lived until age 96 and never remarried.

“She never stopped believing that he was going to come home,” said her grandson, Scott Jefferson.

Memorial Day 2013: The Search

As Memorial Day approached twelve years ago, Althaus asked his mother for names of relatives who died in World War II.

Althaus, a political science and communications professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, became curious while researching World War II casualties for work. His mother gave him the name of her cousin Thomas Kelly, who was 21 years old when he was reported missing in action.

Althaus recalled that as a boy, he visited Kelly’s memorial stone, which has a bomber engraved on it. He began reading up on the lost plane.

“It was a mystery that I discovered really mattered to my extended family,” he said.

With help from other relatives, he analyzed historical documents, photos and eyewitness recollections. They weighed sometimes conflicting accounts of where the plane went down. After a four-year investigation, Althaus wrote a report concluding that the bomber likely crashed off of Awar Point in what is now Papua New Guinea.

This undated photo shows the World War II B-24 bomber, Heaven Can Wait, that went down in the waters of Hansa Bay, Papua New Guinea in 1944. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency via AP)

The report was shared with Project Recover, a nonprofit committed to finding and repatriating missing American service members and a partner of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, or DPAA.

A team from Project Recover, led by researchers from Scripps Institution of Oceanography, located the debris field in 2017 after searching nearly 10 square miles (27 square kilometers) of seafloor.

The DPAA launched its deepest ever underwater recovery mission in 2023.

A Navy dive team recovered dog tags, including Darrigan’s partially corroded tag with the name of his wife, Florence, as an emergency contact. Kelly’s ring was recovered. The stone was gone, but the word BOMBARDIER was still legible.

And they recovered remains that underwent DNA testing. Last September, the military officially accounted for Darrigan, Kelly, Sheppick and Tennyson.

With seven men who were on the plane still unaccounted for, a future DPAA mission to the site is possible.

This October 2017 photo shows wreckage of the B-24 Liberator bomber, Heaven Can Wait, lying on the seafloor where it went down during World War II in Hansa Bay, Papua, New Guinea. (Courtesy of Project Recover via AP)

Memorial Day 2025: Belated Homecomings

More than 200 people honored Darrigan on Saturday in Wappingers Falls, some waving flags from the sidewalk during the procession to the church, others saluting him at a graveside ceremony under cloudy skies.

“After 80 years, this great soldier has come home to rest,” Darrigan’s great niece, Susan Pineiro, told mourners at his graveside.

Darrigan’s son died in 2020, but his grandson Eric Schindler attended.

Darrigan’s 85-year-old niece, Virginia Pineiro, solemnly accepted the folded flag.

Kelly’s remains arrived in the Bay Area on Friday. He was to be buried Monday at his family’s cemetery plot, right by the marker with the bomber etched on it. A procession of Veterans of Foreign Wars motorcyclists will pass by Kelly’s old home and high school before he is interred.

“I think it’s very unlikely that Tom Kelly’s memory is going to fade soon,” said Althaus, now a volunteer with Project Recover.

Sheppick will be buried in the months ahead near his parents in a cemetery in Coal Center, Pennsylvania. His niece, Deborah Wineland, said she thinks her late father, Sheppick’s younger brother, would have wanted it that way. The son Sheppick never met died of cancer while in high school.

Tennyson will be interred on June 27 in Wichita, Kansas. He’ll be buried beside his wife, Jean, who died in 2017, just months before the wreckage was located.

“I think because she never stopped believing that he was coming back to her, that it’s only fitting she be proven right,” Jefferson said.

Genghis Khan

The worst version of myself

- Joined

- Apr 7, 2013

- Messages

- 46,707

Sounds about right.

Irving Cowboy

DCC 4Life

- Joined

- Feb 7, 2014

- Messages

- 3,713

Seconds to Spare: A Sailor’s Fight for Life in the Eye of the Storm

05 June 2025

From COMNAVAIRLANT Public Affairs

Norfolk, Va. – The order to cancel evening flights came down at 8:15 p.m. on April 7, 2025, a reprieve from a rapidly approaching storm that promised to shroud USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) in darkness and rain. But before the last helicopter could be secured, a different kind of emergency ripped through the ship – a Sailor collapsing, an emergency call over the 1MC, and a desperate race against time and Mother Nature.

Cmdr. Sean Rice, the executive officer assigned to Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron (HSC) 9, was preparing for a 9:00 p.m. flight when word came that the last two cycles of the evening were canceled. Severe convective weather was threatening the divert airfields, making conditions too dangerous for flight operations. The storm was moving faster than anticipated, and its arrival at Ford’s location was imminent.

Abruptly, the rapid, insistent peal of bells reverberated through the narrow passageways of the ship, and “Medical emergency, medical emergency!” was called over the 1MC. The ship’s medical team sprang into action. When they arrived at the gym, they found Sailors already performing CPR on an unresponsive Sailor. The patient had been running on the treadmill, then stopped, convulsed and collapsed on the floor between rows of equipment.

Lt. Elizabeth Uecker, Ford’s physician assistant, called Lt. Carlos Robles, the ship’s nurse, from the scene.

“It’s happening. We are doing CPR. We need medications, and you need to get up here!”

Robles’ boots pounded the floor as he ran to the crash cart in Main Medical, pulled medications and told the nurse anesthetist to grab his gear for intubation.

In the gym, the Medical Response Team (MRT) was on round six of CPR. They worked in sync, their movements precise and practiced. As rescue breaths were given, the defibrillator pads were placed. The first rhythm check came back—ventricular fibrillation, no pulse. As the defibrillator charged, every pair of eyes in the room watched the monitor. The shock was delivered and CPR resumed. Another check—no pulse.

After 15 rounds of CPR and the administration of epinephrine, the patient’s pulse returned signaling they could now be moved down to Main Medical.

After intubation and stabilization, the Corpsmen swiftly transported the patient through the ship to Main Medical. The path ahead was a gauntlet: across the gym, down a ladderwell, through the maze of aircraft in the hanger bay, into the medical staging area elevator and finally down to the 2nd deck and into Medical. There, Lt. Cmdr. Jordan Robinson, the ship’s surgeon, immediately took control as the decision was made to transport the Sailor off the ship to the nearest Level 1 trauma center. The medical team reassessed the vital signs, confirmed and secured the airway, started necessary medications and quickly completed lab work to stabilize the patient for the flight ahead.

In the Combat Direction Center, an undercurrent of tension ran through the group as flight preparations kicked into overdrive. Capt. Christopher Williams, Ford’s executive officer, moved with focused urgency to mobilize the medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) coordination team. Several departments — Operations, Security, Weapons, HSC-9, and Destroyer Squadron (DESRON) 2 — were called in to execute a plan.

The storm still loomed, its unpredictability casting doubt on whether the helicopter would be able to make it to Shands Medical Center in Jacksonville, Florida, at all. Each choice involved a calculated risk.

Lt. j.g. Melvin Williams, Rice’s co-pilot, and Naval Aircrewmen 3rd Class Haevinn Kahala, both assigned to HSC- 9, sprinted to the aircraft. They were tasked with preparing the helicopter and ensuring the cabin was ready for a litter-bound patient in desperate need of care. At the same time, two of the squadron’s seasoned medical professionals—Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Damiano Bonadonna, and freshly-qualified aircrew paramedic Naval Aircrewmen 2nd Class Sean Winterburn, volunteered to join the

“The HSC-9 pilots and crew had the helicopter ready and spinning long before we were even close to sending the patient,” said Cmdr. Kristina O’Connor, Ford’s senior medical officer. “They were monitoring the storm with precision, getting constant updates on the weather and adjusting their flight path on the fly. Once the patient was loaded, without hesitation they were off.”

Everything was set in motion. The storm was the only thing standing between the crew and their destination. Shands Medical Center was identified as the closest safe haven, but even as they plotted the course, weather reports from Florida’s divert airfields showed conditions were rapidly deteriorating.

The ship’s meteorologists delivered vital updates. The radar painted a dire picture: a violent line of storms was churning from the coast of the Carolinas south to Florida, positioned squarely between the ship and Jacksonville. But there was a break in the storm’s progression that allowed for a narrow opening in the weather, and the crew saw their chance to move southward toward the city. Rice and his crew chief, Naval Aircrewman 1st Class John Kainoa, gathered all required information and proceeded to the helicopter.

At 10:45 p.m., the crew launched into the night sky, immediately greeted by sheets of rain, intense lightning, and towering clouds. Engulfed by the storm, they aimed for a tiny sliver of clear sky – the helicopter’s only visible path. An additional airborne helicopter from Helicopter Maritime Strike Squadron (HSM) 70 provided real-time weather information for Rice’s crew to avoid the storm and maintain visual conditions as long as possible. Despite their vital assistance, the weather provided no choice but to punch through the rain and clouds and proceed via instrument navigation.

Robles, Bonadonna and Winterburn worked to stabilize the patient during the transit. The patients’ vital signs were deteriorating. While battling turbulence that shook the aircraft violently and operating under the dim glow of limited light, they administered life-saving medication with precision, their hands steady despite the chaos around them. Every decision, every movement, was deliberate as they worked in near darkness with unwavering focus.

With 60 nautical miles left to go, sudden turbulence tossed the helo from side to side, lightning intensified, and the headwind roared to nearly 50 knots, but the patient’s condition demanded they press on. Rice called for deviation - a plea for a lower altitude from the shore controlling agency. Even though they might lose radar contact, a descent to 3,000 feet was ordered. Rice then requested a further drop to 2,000 feet, demanding maximum performance of the aircraft and knowing the calculated risks he needed to take to deliver his crew and their patient safely.

Slowly, the headwind began to fade, and the sky began to quiet as the lightning retreated. As the clouds began to part, the dim, distant lights of the Jacksonville skyline emerged through the haze— offering a promise of safety amidst the storm. But the situation remained critical. Shands Medical Center came into view, and the crew executed a flawless approach. The aircraft touched down at 12:07 a.m. The medical team swiftly transferred the patient to Shands’ Intensive Care Unit.

“In more than 3,000 hours of military flying experience, this was by far the most challenging and dangerous weather conditions I have ever encountered on any flight, much less one at night, long-range, from ship,” said Rice.

The Sailor’s initial prognosis was less than 15% chance of survival. But the crew refused to concede, and despite the odds, the patient is now recovering. It was a mission that could have ended in tragedy, but instead became a testament to courage, skill, and teamwork.

Rice and Williams both received Navy Commendation Medals, and Robles, Kainoa, Kahala, Winterburn and Bonadonna were awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal on April 13th, 2025, in recognition of their life-saving efforts and heroic actions.

(U.S. Navy story written by MC2(SW/AW) Julianna J. Lynch)